Climate and conflict

New research demonstrates connections between climate change and civil unrest among the ancient Maya

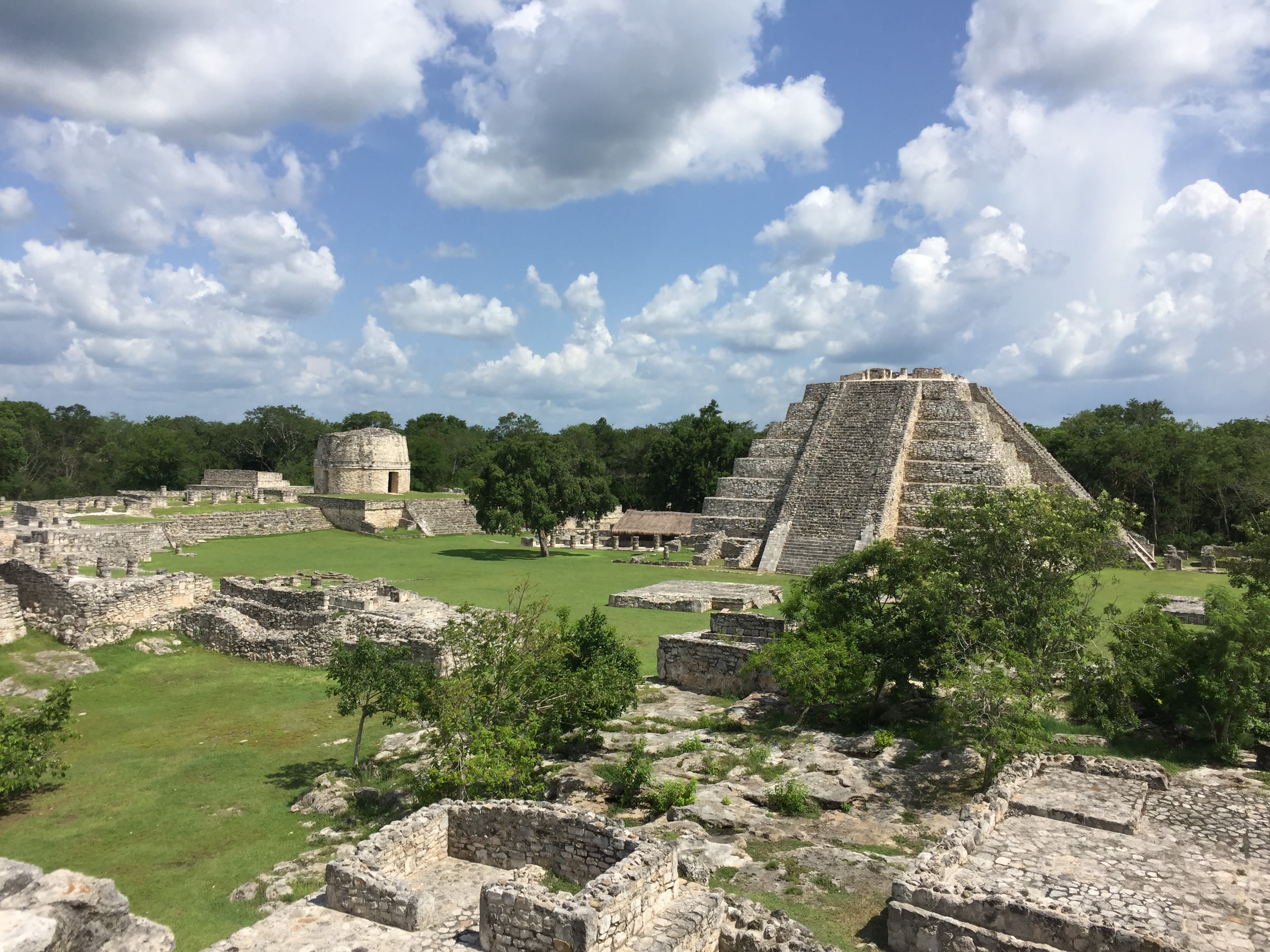

Mayapán was the largest Maya city from approximately 1200 to 1450 CE. As an important political, economic and religious centre, it was the capital of a state that controlled much of northwestern Yucatan in present day Mexico.

The city was abandoned after a long period of population decline, conflict and political rivalries — reaching a peak between 1441 and 1461 CE. Some have thought that inherent instabilities meant the city was doomed to fail, but now a team of scientists have shown that a long period of drought was key in deciding its fate.

The findings were reported in Nature Communications and led by Douglas Kennett of UC Santa Barbara and David Hodell of the University of Cambridge. The project brought together anthropologists, bioarchaeologists, historians and palaeoclimatologists in order to assesss the role of climate in the violent collapse of Mayapán.

“Drought-induced civil conflict had a devastating local impact on the integrity of Mayapan’s state institutions that were designed to keep social order. However, the fragmentation of populations at Mayapan resulted in population and societal reorganization that was highly resilient for a hundred years until the Spanish arrived on the shores of the Yucatan,” said Kennett.

The entrance to the Ch’en Mul cave. Credit Khristin Landry.

The entrance to the Ch’en Mul cave. Credit Khristin Landry.

A cave directly beneath the city’s central plaza is where scientists— including Cambridge earth scientists David Hodell, Stacy Carolin, Dan James and Tom Spencer — found evidence of this ancient drought.

They extracted climate data from a stalagmite which formed as water dripped onto the cave floor over thousands of years.

“We have direct evidence of warfare from the archaeology,” said Hodell, “What’s unique is that we can link this detailed social record to the paleoclimate history, using data collected from almost directly beneath the central Plaza at Mayapán – no other studies have done that before.”

The entrance to Ch’en Mul cave

The Ch’en Mul cave, which is actually a sinkhole known locally as a cenote, was likely an important water source for the ancient Maya and possibly used for sacrificial offerings.

Stalagmites inside the cave formed as mineral-rich water slowly dripped onto the cave floor — each successive drop adding another layer of calcium carbonate. Scientists can harvest climate data from them by measuring stable isotopes of oxygen and carbon in the calcite. Uranium-thorium dates on the stalagmites also tell scientists when the climate and landscape changed.

Stacy Carolin, a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Earth Sciences, counted the annual calcite layers of the stalagmite and then dated specific points in the record at the University of Oxford. Carolin found the stalagmite from beneath the city grew in two phases: the first layers deposited between 1020 CE and 1410 CE, followed by a halt in growth for nearly two centuries before continuing again between 1600 — 1930 CE. This missing window, explains Hodell, may have resulted from the cave drip water drying up when drought struck Mayapán.

Growth layers inside the Ch’en Mul cave stalagmite. Note the dark band representing the drought. Dated intervals are indicated and the red line shows a change in calcite composition following the drought. Credit: David Hodell.

Growth layers inside the Ch’en Mul cave stalagmite. Note the dark band representing the drought. Dated intervals are indicated and the red line shows a change in calcite composition following the drought. Credit: David Hodell.

They also found that the chemistry of the stalagmite changed after the hiatus; the youngest phase of growth is a different form of calcite known as aragonite — possibly because dry conditions decreased the drip rate and altered the chemistry of the cave drip waters.

Sampling the Ch’en Mul cave stalagmite.

The researchers expanded their investigation of the missing time window outwards to a sinkhole lake, Aguada X’caamal, which is located roughly thirty kilometres west of Mayapán.

Hodell and colleagues had collected sediment cores previously from the bottom of the lake. Re-dating the sequence revealed that at around 1413 – 1441 CE a microscopic foraminifera species appeared in the sediment profile that prefer saline conditions, suggesting lake levels dropped as the result of the same drought recorded in the cave.

Sinkhole lake, Aguada X’caamal

Sinkhole lake, Aguada X’caamal

Hodell has been working on climate records from the region for the last two decades and collected samples of the Ch’en Mul cave stalagmite in 2005. The record was first analysed by undergraduate student Tom Spencer as part of his part III project in the Department of Earth Sciences.

“We are working on several other stalagmites from Ch'en Mul cave and the goal is to find a specimen that grew through the missing time window – if we can get detailed data from that window we can reconstruct the severity of the drought and it’s timing with greater certainty,” said Hodell.

Palaeoclimatologists from Cambridge’s Godwin Lab are about to visit the cave again to make the first detailed map of its layout and install data loggers that continuously take temperature, humidity and drip rate readings. The work is part of The Leverhulme Trust Speleothem Project, which aims to understand interactions that may have occurred between the ancient Maya and their environment.