Alumni News

07/02/2024

Professor Aral Okay

It is with sadness that we share the news of the passing of Professor Aral Okay. A PhD student in the Department during the 1970s, his initial papers established him as a world-class petrologist and brought the geology of Turkey to the attention of the international community. You can read more about Professor Okay's life and research on the memorial here.

05/09/2023

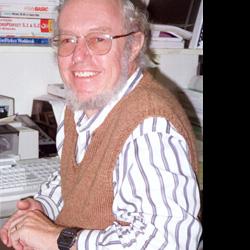

Special issue celebrates the work of Tony Dickson

A special issue of ‘The Depositional Record’, a journal of the International Association of Sedimentologists, celebrates the work of Cambridge Earth Sciences’ Dr Tony Dickson.

Tony Dickson, who joined the Department of Earth Sciences in 1981, is known not only for his legacy of innovative research on carbonate diagenesis, but also for his contributions as a mentor and teacher over more than 50 years. He taught carbonate sedimentology to generations of Cambridge students. He also ran the Dorset field trip; the evening seminars that he introduced becoming standard practice on all Department field courses. Even more memorable were his field courses to West Texas, New Mexico and the Bahamas.

Group photo, 2004. In front of the world famous Permian Reef, Guadalupe Mountains on the Texas/New Mexico border. Present are leaders Art Saller and Tony Dickson, assisted by Nigel Woodcock.

The special issue, which was authored by colleagues and a former PhD student, explores how Tony’s pioneering work transformed our understanding of carbonate rocks and in turn paved the way for modern analysis of carbonates.

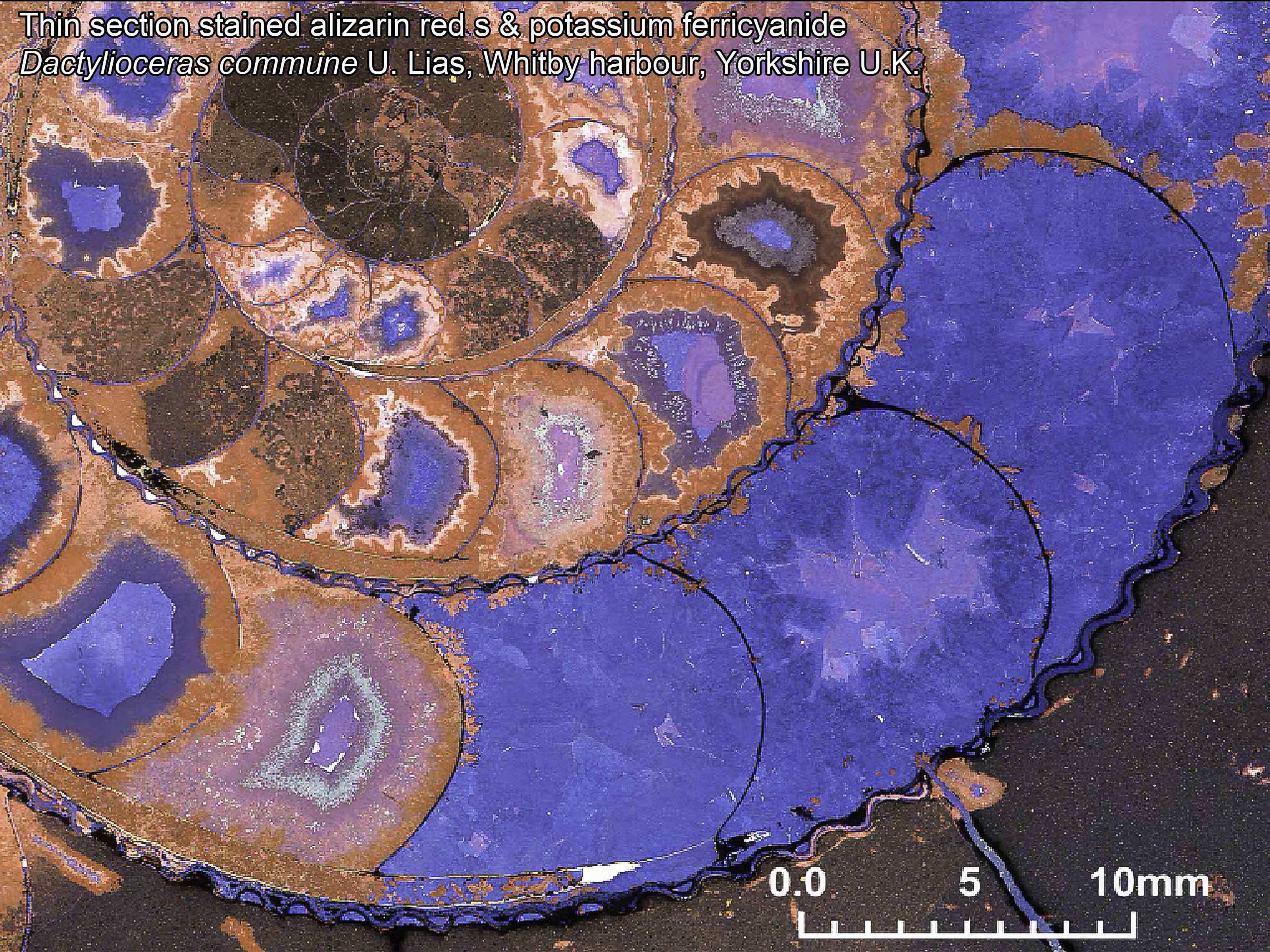

One of his early breakthroughs, described in Nature in 1965, was the development of a staining technique to distinguish calcite, dolomite and their iron-rich variants in thin sections. Tony originally developed this method as part of his PhD and it is still used today, including by our Part II mapping students.

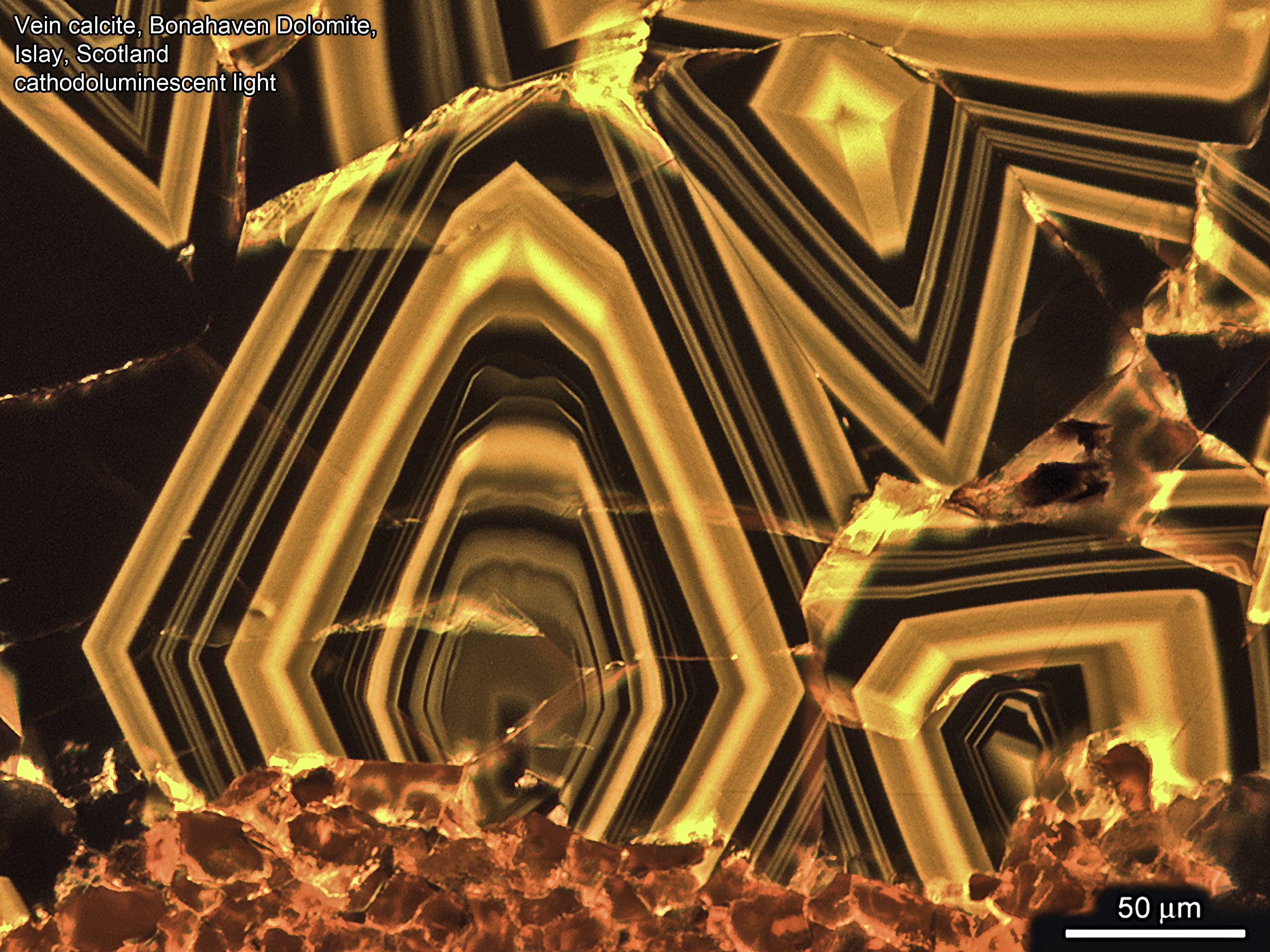

By the 1980s, Tony was exploring carbonate crystal growth and zonation using early geochemical techniques, including cathodoluminescence, stable isotope and trace element analysis.

Employing state-of-the-art analysis has been a common theme of his career. In fact, in this special issue Tony, together with Peter Swart, re-examine one of his published datasets with a new technique and disprove their earlier publication. Tony also has a YouTube channel where he continues to publicize his latest research.

Thin section cathodoluminescence image, zoned calcite cement growing centripetally into a small vein, Bonahaven Dolomite, Dalradian, Islay, Scotland. Below: Stained thin section showing variation in the fill of an ammonite’s camerae; brown - lime mud ,red - non-ferroan calcite, and mauve, purple and blue ferroan calcite with varying amounts of ferrous iron present. Both credit: Tony Dickson.

A message from Head of Department, Richard Harrison

I am delighted to announce and introduce our incoming Business Operations Manager, Alison Cook, who joined us at the start of November. The role of Business and Operations Manager is an evolution of the Department Administrator role and Alison is taking over from Andy Buckley who retired in September.

Alison has been within the University of Cambridge for a decade and has spent the last four years with the Professional Services Support Team, gaining experience across all six Schools. She was, most recently, interim Business Operations Manager at DAMTP. She has a BA Hons in English Literature and Art History and an MBA from the University of Bath.

Alsion also enjoyed a varied career before joining the University, working in the Civil Service, She's worked for the police and in local government, and had several years in IT project management, including a year in Hong Kong working for Cathay Pacific Airlines. She lives in Cambridge 'with my husband and 15 year old son and spend a lot of time watching, supporting and taxi-ing between various rugby fixtures.' She enjoys painting, visiting galleries and museums, and lots of outdoor activity (recently having climbed Helvellyn via Striding Edge).

Alison says:

"I am very excited to be joining Earth Sciences and can’t wait to start. After four years moving around the University, I am really looking forward to being part of a team and getting to know and making a difference to all aspects of the Department. I know Andy Buckley will leave a huge hole and I look forward to stepping into his shoes and supporting the fascinating work of this inspiring Department."

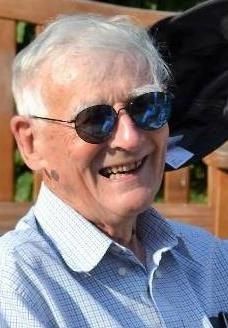

Andy Buckley retires as Department Administrator

Interview with Cara Hanman.

After gaining his degree from Birmingham and his PhD from Nottingham, Andy Buckley came to the Earth Sciences Department at Cambridge University, in his own words, ‘more or less straight after finishing my PhD.’ He admits, with a chuckle, that he had to take a few days off to return to Nottingham to do his viva.

It was shortly before Christmas, 1982 and the post he accepted was an 18 month contract under John Long to run the Electron Probe lab. In spite of his only previous trip to Cambridge being for the interview, Andy clearly threw himself into Department life. He learnt from the likes of Stuart Agrell and Graham Chinner, worked in parallel to Pravin Patel and also provided IT support for the Downing site before the first computer officer was appointed. He easily recalls this pre-PC time when the only people using IT relied on a mainframe or BBC micro or an Amstrad – all in a time before the internet!

Andy, on the left, and others enjoying a lunch break at Glen Sannox, 1996

It’s one of the first things you notice when talking to Andy – he’s very knowledgeable and very generous with that knowledge. It takes a little longer to learn that Andy is incredibly humble. Andy’s own description of the task before him in 1982 is that the “job involved nursing the computer system which was used to convert the x-ray count rates from the probe into useful mineral analyses. The system had 2 disk drives which held 8 inch disks with 500kb storage – but the computer memory was only 32kb and you had to write efficient code to fit into that amount of memory!” After I interviewed him, I was talking with Michael Carpenter about Andy’s past life in the Electron Microprobe lab. Michael’s observation shows how humble Andy has been: "Andy is a genius when it comes to creating interfaces that allow computers and scientific instruments to talk to each other. His work in this area, first on the electron probe and then for the mineral physics group, contributed substantially to the long tradition in the department of building new and unique equipment. Those of us who benefited from his particular technical expertise and creativity have good reason to be especially grateful to Andy for his generous help and support, without which our instruments would never have run."

Andy and students on the Arran field trip at Rubha Airig Bherig, 1996

Ron Oxburgh was head of the recently amalgamated department at the time Andy joined. Even though there was still a Min & Pet library in the South Wing and a Geology library in the North Wing, a lot of the other physical changes that went with Ron’s task to bring together those two Departments with the Department of Geophysics had already been undertaken. Now those two library collections have been joined into one library, and the old library spaces are used as offices and labs. Changes to the building happen all the time – Andy has seen many alterations since 1982 and knows about many others that pre-date his arrival. He has a valuable interest in what different spaces were used for ‘once upon a time’. In his most recent office there is a cupboard that used to be an egress to the reception foyer of the Department. Now it has floor to ceiling shelves and many files dating back to his predecessor, Margaret Johnson’s, time that prevent anyone making a hasty exit that way. The office also has a glorious tiled antique fireplace and we spend a bit of time talking about the likelihood of other such fireplaces existing behind panelling in different offices in the building.

As well as being Department Administrator for the past 12 years, Andy has also run supervisions at Fitzwilliam College. Even though he is yet to find a new home for the rock collection he used for this teaching, he insists that he has also retired from that role. Asked about being a supervisor, Andy says that ‘Earth sciences has changed over the 40 odd years I’ve been working and it was a good way of keeping up with what was going on. The Fitz students were a great bunch. Some of them did the IA course and left to do Chemistry or Physics and then came back to do their PhD; it was nice to see them coming back.’

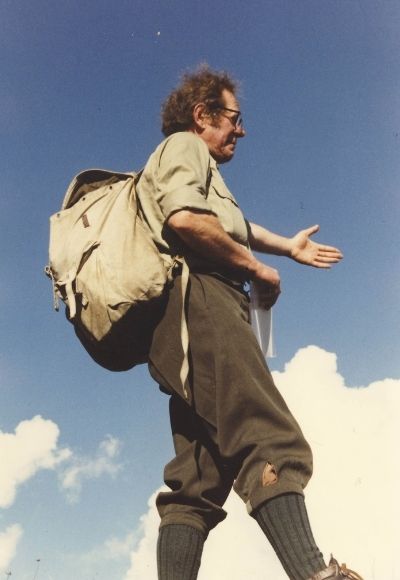

Andy in the field.

As well as students, Andy talks about the research students and staff who have come to Cambridge Earth Sciences from other courses or other universities. Again, his broad knowledge leads to an interesting conversation on the cross-discipline work that is happening at Cambridge now. He observes that ‘A lot of the great advancements in science happen because of people from different disciplines talking together.’ If you are new to the Department, 30 minutes talking with Andy will give you a strong flavour of the friendly atmosphere that pervades the building.

To further reinforce this impression, when asked the clichéd question of what he will miss, he responds, ‘I’ve been here 40 years, and it’s a friendly place… [I will miss] the people and things like the Alumni Days and special occasions. It’s been a pleasure to simply get to know such a wide range of people who have come from such a diverse range of backgrounds.’ On the topic of notable moments from his time as Department Administrator, Andy observes that the big challenges kept the role interesting. Things like dealing with having people marooned on the Spanish field trip when Eyjafjallajökull erupted in 2010 causing flights to be grounded, and when the 2001 Foot and Mouth outbreak made UK-based fieldtrips impossible.

Andy in Dorset in 2009.

When asked how he’d describe his tenure as Department Administrator, Andy’s response is that he always saw the role as ‘making sure the academic staff can do what they’re good at – do the earth sciences, do the research, do the teaching – and to reduce the burden of administration that falls to them. The aim really is to make sure that everyone knows what they’re doing and they feel valued.’ He observes, ‘It’s always been quite satisfying to see members of a team progress, move on to more senior roles and learn new things.’

On Andy’s official last day in the Department, his partner (Dr Liz Hide, the Director of the Sedgwick Museum), posted a tweet in acknowledgement. On it there was a photo from a fieldtrip some years ago. It must have been hard for her to choose just one fieldtrip photo because Andy taught on the Arran fieldtrip for about 25 consecutive years, making him well known to many Earth Sciences alumni. As well as Arran, he went on almost every other departmental field course. He’s also been on trips to Northern Pakistan and Newfoundland with research teams. However, he admits to a soft spot for the Arran fieldtrip, not least because it allowed him the opportunity to take a week’s leave after each field trip to indulge his passion for climbing in the Highlands.

Dr Liz Hide's tweet for Andy's last day, featuring a fieldtrip photo and a photo from his leaving drinks

Indeed, Andy has been climbing all over the UK, in the Alps and other places in Europe, and as far afield as Ecuador and the Andes. A highlight was reaching the top of The Old Man of Hoy on his 50th birthday. His future plans don’t stretch to having the next many years mapped out but he assures me climbing will feature significantly. “One of the best times for rock climbing in the UK is when the University exam season is in full swing. I plan to revisit some favourite places in the UK, to take advantage of the rather random winter climbing season in the Scottish highlands and spend more than a week skiing in the spring without having to rush back to the desk afterwards. But I also intend to get further afield; including having a trip to the Indian Himalaya or Nepal and I have a desire to return to somewhere like the Peruvian Cordillera Blanca. And it really helps to still be fit enough to do those sorts of things.”

His next big climbing trip is to Sardinia and, while looking through a climbing guide recently, he found himself getting distracted looking at the geological information of the area. “Once a geologist, always a geologist,” he muses.

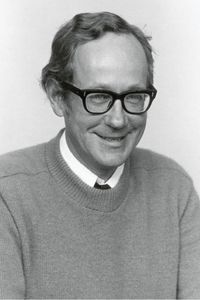

James Jackson "Retires"

For alumni especially, James Jackson is one of the best-known and most energetic members of the Earth Sciences department, and so it comes as a surprise to find that he has reached the official retirement age for academics. Here, the even older Nigel Woodcock looks back on James’s teaching, research and administrative career, and finds out what his plans are for “retirement”.

James's year group listen attentively as Bob Jull and Chris Hughes explain Carboniferous geology in Pembrokeshire in 1975. James is in the khaki anorak, next to the student in the yellow jacket.

James did his first degree in the old Department of Geology in 1973-6. These were the years just after plate tectonics had been formulated – in part up the road at Madingley Rise – but before the subject was deeply embedded in the Geology course. Nevertheless, it was geophysics that most interested James, such that he did a PhD at Bullard with Dan McKenzie on active tectonics in the Mediterranean. After a spell as a post-doc, James was appointed as a lecturer in 1984, in the then consolidated Earth Sciences department. He got promoted to Reader in 1996 and to Professor of Active Tectonics in 2002. This seemingly continuous career record in Cambridge masks the various short-term visiting positions that James held overseas: at M.I.T., Utah, Stanford and Caltech in the States; DSIR and IGNS in New Zealand; and CNRS Grenoble in France.

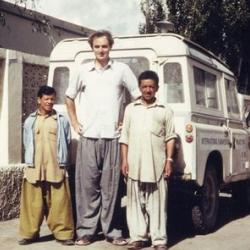

James with his cook and bodyguard on a research trip to the Karakorum in 1980.

James’s research is into how continents deform today. He has done field work throughout the Alpine-Himalayan Belt as well as in New Zealand, Africa and the USA, and has integrated field observations with those from space-based remote sensing and from seismology and geodesy. Many of his over 200 published research articles are widely cited and this research record has attracted prestigious honours: the Bigsby and Wollaston medals of the Geological Society, Fellowships of the Royal Society and of the American Geophysical Union, and the CBE.

James on top of Goat Fell on a 2003 IA field trip to Arran.

However, alumni will know James as much for his teaching activity as for his research record. For many years he taught the opening lecture block in the first year Geology/Earth Sciences course. This was, and remains, a critical series of lectures for recruitment. Some incoming students are still unsure which subject to take as their fourth NST option, and James’s enthusiasm and ability to explain complex Earth processes outshone, to our advantage, lecturers in other subjects. These recruited students might well have met James again on the Arran field trip. If not they would get Part II/III Geophysics teaching from him in both in the lecture room and – more memorably still – on the Greek field trip.

Professors White, Jackson, McCave and Maclennan at Leonidas's monument, Thermopylae on the 2010 Greek field trip.

Beyond Cambridge, James is a popular public science lecturer, most notably through his 1995 Royal Institution Christmas Lecture series on ‘Planet Earth an explorers guide'.

Although James would rather have been teaching or researching, he stepped up in 2008 to do an eight-year stint as Head of Earth Sciences, a job with steadily growing responsibilities and workload. Despite this administrative load, James still found time to supervise graduate students and, between 2012-18, to co-lead the `Earthquakes without frontiers' project: a partnership between UK earthquake scientists and those in countries of the earthquake belt between Italy and China. The aim was to share knowledge, expertise, training and resources to increase societal resilience to earthquakes.

Looking back at his career, James will emphasise the exhilaration of being part of a department that became a world leader by successfully combining research in geophysics, tectonics, petrology, geochemistry and basin analysis. He is particularly grateful for the vision of such as Ron Oxburgh and Dan McKenzie in unifying the three former components of the Earth Sciences department in 1980, and creating the collaborative research climate that has served the department so well.

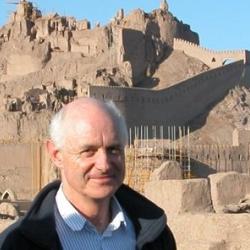

James in Bam, Iran after the December 2003 earthquake.

Looking forward to his career yet to come, he is particularly keen to continue his role in the application of earthquake science to mitigating the earthquake risk in Eurasian countries. His colleagues and former students look forward to seeing James fully involved in departmental life and in alumni events.

Alumni Day and Dinner returns after 3 year hiatus

The Department welcomed Alumni back through the doors on 14th May 2022 for the first Alumni Day since 2019. The programme gave Alumni the chance to hear from current staff and students, walk the halls once again, visit the library, the museum and choose from a number of tours.

Read more about the day here:

Obituaries

Memories of Graham Chinner

The Department is sad to share the news of Dr Graham Chinner’s passing in December 2021. Memories and tributes from Dr Chinner’s colleagues and students are below.

Image copyright: The Master and Fellows, Trinity College Cambridge.

"Graham arrived in Cambridge in 1955 as a graduate student in the Department of Mineralogy and Petrology – known as Min & Pet. Peter joined the adjacent Department of Geology – known as the Sedgwick – as an undergraduate in 1957, so was a colleague of Graham’s for most of his career. Nigel arrive belatedly as a member of staff in the Sedgwick in 1973.

The overriding memory we both have of Graham is of the twinkle in his eye when you mentioned something that recalled an anecdote from his memory. That look and a barely suppressed smile meant that an entertaining story was in the offing, to be told with zest and much laughter. Graham was a great raconteur.

During the firm reign of C.E. Tilley as Professor of Mineralogy and Petrology (1931-61) professional and social mixing between Min & Pet and the Sedgwick was banned. To illustrate this regime, Graham told of the time when, as a graduate student, he had innocently borrowed a microscope from the Sedgwick and was setting of across the courtyard between the two buildings to return it. Tilley spotted him from his first-floor office, flung the window open and yelled “Chinner, where are you going.” Graham explained apologetically. “This time, but never again,” fumed Tilley.

However, Graham’s convivial nature meant that he regularly crossed the departmental boundaries. Most memorably, Graham ran a joint final year Easter field trip to the Scottish Highlands on which Peter shared the teaching on a number of occasions. Peter remembers Graham’s usually cheerful mood despite inclement Scottish weather, but how it could be severely tested by youth hostels that were locked or had frozen pipes, and by his hotel room being above the bar or next to a noisy lift shaft.

Photograph from the Part II Scotland field trip at Easter 1974. Peter Friend is third in the line, Graham Chinner is far right.

Soon after Nigel’s appointment to the teaching staff in 1973, Graham got him appointed as a Lector in Trinity College, to help Graham with the Geology supervision teaching. Graham particularly enjoyed designing exercises and maps for supervisions, all executed in his stylish italic script. Graham also enjoyed dining in college, and on those evenings Nigel heard another range of anecdotes with collegiate rather than geological themes. Graham was also prone to entertain by reciting prose or poetry from memory.

Graham was the Curator of the museum of Mineralogy & Petrology from 1980-1997 when the museum was merged with the Sedgwick Museum. From 1997 until he retired in 1999 he was Curator of Minerals within the Sedgwick Museum.

Graham no longer came in much to the Earth Sciences department after his retirement, but is warmly remembered by his former colleagues and students. We wished that he had written down some of his geological anecdotes as a tangible memorial. Maybe he has…"

- Peter Friend and Nigel Woodcock

"When I was appointed Director of the Sedgwick Museum in 1991 I ‘inherited’ Graham as the long-established ‘Curator of Min & Pet’. Graham was a whimsical character. I never quite knew what he thought of the young upstart who had been appointed, but I was to learn over time that he would quietly, and in a completely unheralded way, make sure that ‘essential oil’ was applied to the bearings of the old locomotive at the appropriate time. At the time of my appointment, Graham was not only teaching in the Department (as well as acting as a curator) but, more critically, held the position of Senior Tutor at Trinity College. The latter connection, and the fact that Adam Sedgwick was an eminent former Fellow of Trinity and indeed its Vice-Master, proved to be vitally important in relation to the acquisition of a series of substantial grants that allowed the Museum to renovate its galleries, its offices and support systems; and to increase its staff complement and their professional training. In several instances, small grants from Trinity (or the Isaac Newton Trust - INT) proved to be the essential ‘leverage’ that encouraged/persuaded other grant awarding bodies to invest in the redevelopment of the Museum. The Whewell Gallery redevelopment was largely funded by Trinity directly, and this was followed by the creation of “Jurassic Pond” and then the major redevelopments of the Mahogany and Oak Wing galleries (the former opened by our alumnus Sir David Attenborough, and the latter by Lloyd Grossman, who was at the time Chair of the Museums & Galleries Commission). The last major redevelopment with which I was involved focused on Darwin and his, largely unrecognised, geological research and was focused on the redevelopment of the western end of the Mahogany Wing. Yet again Trinity/INT provided faith in, and money for, this redevelopment. They awarded me a substantial grant in the mid 2000s that they then put into ‘storage’ for me (thereby increasing its value by earning interest in the intervening years), while I was left to raise a major tranche of funding for the entire project. This project was completed in time for the 200th anniversary celebrations linked to the birth of Charles Darwin held in Cambridge and at Christ’s College in 2009. Graham claimed nothing and said nothing about the support that we received from Trinity across 20 years of sustained growth and redevelopment, but I would be prepared to bet the HoDs wallet on the probability that the Senior Tutor’s influence at Trinity, on the Governing Body and/or College Council was critical when it came to matters of assessing bids from Sedgwick’s Memorial Museum. Graham’s legacy for me and the Museum is that of the quiet, unassuming and largely unsung supporter-benefactor. He obviously had some faith in the Museum’s Director (and his plans and schemes) and we were able to achieve so much because of Graham’s seniority and his ability to deploy quiet and gentle persuasion when most needed. I will miss Graham immensely. When I knew Graham (toward the end of his career) I enjoyed his delightful dry wit and a rather quizzical/cynical ‘eye’ and manner, born no doubt of his varied experiences during his long tenure in Min & Pet and, following the Oxburgh-driven amalgamations that led to the formation of the enlarged Department of Geology (latterly Earth Sciences). Thank you so much, Graham, you were a star."

- Professor David Norman FLS

"Dr Chinner was my director of studies at Trinity when I was an undergraduate. This is a photo (above) of him on the Scottish field trip in 1986, quoting Hamlet from the top of a rock."

- Paddy Gall

"I have happy memories of Graham, especially in the early 1980s - he was always in remarkably good humour when I was working with him on 1A examinations!"

- Simon Kelly (CASP)

You can also read the tributes paid by Graham's colleagues, friends and former students at Trinity College on their website: https://www.trin.cam.ac.uk/news/tributes-paid-to-dr-graham-chinner/

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The department is sad to announce, on September 7th, 2021, the passing of Dr. Chris Harrison.

Christopher G.A. Harrison, 1936-2021

By Peter Swart

Most recently at the Department of Marine Geosciences at the University of Miami, Chris Harrison had been a faculty member at the Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences (RSMAS) since 1967 and was pivotal in the rise of RSMAS to one of the premier marine schools in the world. He was recruited to what was then called the Marine Laboratory at the University of Miami through the efforts of Fritz Koczy and Cesare Emiliani and joined an impressive group of at the time young faculty. In 2015 he retired becoming an emeritus faculty. During his time at University of Miami he served both as chairman (1976-1983) of the Division of Marine Geology and Geophysics, Chair of the RSMAS School Council, and Dean of the School (1986-1989). Outside the school he was very active in the American Geophysical Union (AGU) serving on numerous AGU committees and as general secretary during the period when the AGU grew from a very small niche society to its present position as the most important and dominant geoscience organization extending far beyond its geophysical routes. Other than the University of Miami, the AGU was always one of his passions. Although Chris would become very animated about changes in both organizations with which he disagreed, his love for both surprisingly never wavered.

Chris made his career in the US, but his trip to North America in the early 1960s was not his first venture to that continent. Chris was a child of the second World War, and like many other youngsters at the time was evacuated with his brothers and mother to Massachusetts in the US to avoid bombing and possible invasion, while his father remained behind working on the war effort. One of his many stories involved the return of his family back to the UK during a period in which submarines were still very active in the Atlantic. His mother had decided to return to the UK and the news of her decision had not reached Chris’s father until the convoy had already set sail from the US. According to his father there had just been a major increase in German submarine activity and the convoy was lucky to escape.

After the war, life resumed slowly to normal in the United Kingdom with rationing and national service still in effect. Chris completed his national service in the British Army Corps of Royal Engineers (1955-1957) as a second Lieutenant and was posted all over the world including India, Japan, and Korea.

Afterwards Chris attended the University of Cambridge where he completed his BA in 1960 and then studied paleomagnetism for his PhD (1966) in the Department of Geodesy and Geophysics, at Madingley Rise. This and his later postdoctoral work at Scripps Institution of Oceanography contributed to our understanding of secular variations in the Earth's magnetic field and the origin of magnetic anomalies. Perhaps his most important contribution was the discovery that sediments could record the magnetic field of the Earth, published in Nature in 1964. This finding was seized on by others and was one of the important proofs of the theory of plate tectonics. He was very active in the early days of the Deep-Sea Drilling Project and represented the Rosenstiel School on many of the advisory panels for that program and its successor the Ocean Drilling Program.

Later he published papers on a wide variety of geophysical topics related to plate tectonics, sea level change, and rates of continental weathering and mountain building. Cesare Emiliani, perhaps the most important scientist that has worked at the University of Miami, classified Chris as one of the 290 most influential scientists of all time, a list that included amongst many others Pythagoras, Copernicus, Descartes, Darwin, Einstein, Curie, and Hawking. His last paper was published in July 2021 and summarized from his personal view point the history of the theory of plate tectonics and importance of the Earth’s magnetic field in the development of this theory.

Chris was also a prolific educator having served as the principal advisor for over 30 MS and PhD students, many of whom later became important researchers and educators. During his career Chris, Martha and their family were more than generous, opening their home to foreign students during festive events such as Christmas and Thanksgiving, holding legendary defense parties at their house in the deepest jungles of Coconut Grove, parties which more than often ended up in the swimming pool, and organizing numerous canoe trips throughout the Everglades and South Florida for the Department.

Chris leaves behind his wife Martha, two children Ariel and Ewen, and grandchildren, Rowan, Helen, Phoebe, Rosie. They and his colleagues will miss him greatly.

A full version of this biography is avaialble on the Geological Society's website.

Michael George Bown

5th February 1928 - 29th July 2021

By Michael Carpenter

Alumni and friends of the Department will be sad to hear of the death of Mike Bown at the age of 93. For generations of students, going back to the days of the old Department of Mineralogy and Petrology, Mike will be remembered with great affection as a dedicated and enthusiastic teacher of crystallography and mineralogy. Those of us who had the good fortune to be on the staff with him will also remember his warmth and generosity as well as his sharp wit and invariable good humour.

Mike was an undergraduate at Clare College, coming up in 1946. He had been awarded a scholarship to read Natural Sciences and chose Physics in Part II. He completed two years National Service before returning to the Cavendish in 1951 for his PhD in the Crystallography Laboratory, which was run by W.H.Taylor. These were the last years of Sir Lawrence Bragg's tenure as Cavendish Professor, and still very much a pioneering time for crystal structure determination before the advent of 4-circle diffractometers and computers. Mike worked on intermetallic compounds for his PhD (1955) and his first papers (1956) were on the structures of Al-rich ternary alloys of Al and Cu, with Fe, Co and Ni.

W H Taylor had a long standing interest in the structures of silicate minerals and this must have been at the forefront of the mind of the then Professor of Mineralogy and Petrology, C.E.Tilley, when Mike was appointed to a University Demonstratorship. Another crystallographer from the Cavendish crystallography group, Peter Gay, was also appointed as a University Demonstrator in the Department at about the same time. Their joint publications from this period, either as Gay and Bown or Bown and Gay, reflect a close collaboration based on the use of single crystal X-ray diffraction to explore the complex structural relationships found in natural plagioclase feldspars. "The reciprocal lattice geometry of the plagioclase feldspar structures" (Bown and Gay, 1958, Zeit. Krist. 111, 1-14) is a definitive summary of the different structure types found in both natural and experimental samples. It has provided the language and starting point for almost all attempts to rationalise the properties and remarkable behaviour of one of the most important groups of rock forming minerals in the Earth's crust. Mike also started his work on pyroxenes, using X-ray diffraction to characterise orientation relationships in crystals with exsolution textures. He must have been influenced by wider interest at the time in rocks from the Skaergaard intrusion, East Greenland, leading to another classic work based on the study of 50 crystals: "An X-ray study of exsolution phenomena in the Skaergaard pyroxenes" (Bown and Gay, 1960, Min. Mag., 32, 379-388). These papers presaged a worldwide explosion of interest throughout the 1960's and 1970's in the microstructures of minerals, as observed and analysed using transmission electron microscopy, with another of Mike's colleagues in the Department, Desmond McConnell, leading the way.

After two years as a Demonstrator in the Dept. of Geology and Mineralogy in Oxford, Mike returned to Cambridge to take up a Lectureship in Mineralogy and Petrology. His interests in feldspars and pyroxenes continued and he was one of the first crystallographers to examine lunar samples famously brought to Cambridge from the USA by Stuart Agrell. Although only an abstract, another memorable paper from this period was: "Deerite, Howeite and Zussmanite, three new minerals from the Franciscan of the Laytonville District, Mendocino Co., California" (Agrell, Bown and McKie, 1965, Am Mineral 50, 278) - linking the names of six British mineralogists who are fondly remembered by all who knew them.

In the same year that Mike was appointed to a University Lectureship, 1961, he was elected to a Fellowship in Clare College. He served there as a Tutor from 1965 to 1971, then as the Director of Studies for Natural Sciences, an onerous task that he was renowned for doing meticulously. He acted on the full range of college committees until he retired in 1995, and was known as the person who asked the awkward question that others were avoiding. Mike continued to play an active role in college life for a further two decades.

Mike's life was cruelly disrupted by the untimely death of his wife, Hilary, in 1973. After that he devoted himself firstly to his family and secondly to his college and teaching. Eulogies delivered at his funeral affirmed him to have been a devoted father and grandfather, and a much loved colleague at Clare.

The annual report of the Department of Earth Sciences for 1995-96 notes that Mike "formally retired from his University Lectureship but immediately returned to continue teaching mineralogy". This reflects perfectly the period of his life that the generations of alumni will remember when, above all, he enjoyed the company of young people.

Over the years he lectured regularly to IA NST students in "Crystalline Materials" (the course shared with the Dept. of Materials Science and Metallurgy), as well as to first and second year geologists. His deep knowledge of crystallography was shared with smaller groups in specialist IB and part II courses (Crystalline State) - including a definitive course on crystal physics. His cravat provided a distinctive and trademark appearance, and his many jokes occasionally strayed from political correctness. Everyone who was taught by Mike will have their own memories, most of which will involve his knowledge, his humour and his sense of fun.

Mike served and interacted with the wider mineralogical community with typical modesty and selflessness as Secretary of the Mineralogical Society (1984-89) and as the first Secretary of the European Mineralogical Union (1988-92). He had two periods of sabbatical leave in the USA, firstly at Carbondale, Illinois (1965) and then at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, Blacksburg, Virginia (1973) where he was remembered as a fine crystallographer and friend for many years afterwards. He also spent two periods of sabbatical leave teaching mineralogy at the University of Zimbabwe in Harare.

Part of the Sedgwick Club photograph, 1964, showing Mike (checked tie, back row) in the early days of his time as a Lecturer in the Department of Mineralogy and Petrology. (On his right is a youthful looking Chris Jeans).

Read more about Mike Bown's seminal work on the Single Crystal X-ray diffraction technique here.

John Smallwood (Earth Sciences 1990-97)

We're very sorry to report the news that John Smallwood died in a cycling accident close to his home on Saturday 17 April 2021.

The Department heard the news from John's friend and postgrad colleague, Rob Staples, who wrote: “'I received the tragic news as I sat in my office, where his beaming smile looks down on me, from a picture of him sitting on the Aletsch glacier, where he had just led my wife and me on another successful day of climbing – one of numerous days I have shared with John and his family over the last 30 years. John was a polymath – an accomplished academic, a capable musician, a phenomenal endurance athlete, a skilled mountaineer, a man of strong Christian faith, but, most importantly, a loving, generous and humble man; whenever you met John, you felt better for it. He was a wonderful, multi-faceted man, who enriched all our lives. He will be sadly missed and our thoughts go out to Suki and the boys.”

Those of us in the Earth Sciences Department who remember John echo Rob's sentiments. John was an undergraduate in the Department from 1990 to 1993 and then a postgraduate from 1993 to 1997, studying the Faeroe–Iceland Ridge under Professor Bob White. John later worked for Hess and other oil companies in the UK, Malaysia and Australia, but continued to publish (non-industry) academic papers. He won the Geological Society Young Explorer award in 2005.

At University, John led a busy life with a wide circle of friends in the Department, at Sidney Sussex and later Darwin Colleges, and elsewhere around the University. John had a passion for all the eclectic opportunities life throws up: not only did he excel academically, but he was also Sidney Sussex Boat Club captain and a member of a varsity-winning Cambridge University lightweight rowing crew. John also played in a jazz-band, led youth work in his church, and regularly visited the mountains that he loved so much.

John was an amazing endurance runner, whether that was fell running (winning occasional mountain marathons, and completing the renowned 'Bob Graham Round'), or flying to New York to push his disabled boss around the New York marathon in a standard NHS wheelchair in well under four hours! In 2014, he even represented Great Britain at the world veteran Duathlon championships.

John was well-loved, cheeky at times, almost always smiling, but certainly always caring, positive, and nurturing towards all those around him. John leaves his wife Suki, and three sons.