Submitted by Administrator on Mon, 20/01/2020 - 10:17

A single fossil bone found in Japan is ruffling a few feathers in the world of avian palaeontology. It belongs to a relative of the little auk or dovekie, today the most common seabird and top avian predator in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans. At around 700,000 years old, the fossil’s presence in Japan indicates that during the ‘Ice Age’, the little auk had a much wider range that extended into the Pacific. Discovered by Junya Watanabe of the Department of Earth Sciences in the University of Cambridge and colleagues from Japan’s Kyoto University, the find raises the question of why such a successful, competitive and adaptive seabird should have suffered such a significant reduction in range.

The little auk today

Seabirds are top predators in the world’s seas and oceans where they feed on fish and a host of invertebrates from shorelines to the mid ocean waters furthest from land. The abundance of this food supply means that even as top predators, seabirds can be remarkably numerous. But their abundance is dependent on a number of environmental factors. These factors can fluctuate rapidly in oceanic situations, especially during periods of climate instability, such as ice ages. Today, the shores of the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans are home to an estimated 37 million nesting pairs of little auk, technically known as Alle alle.

One of the problems for palaeo-ornithologists is the paucity of the fossil record of seabirds. Their terrestrial nesting sites are normally coastal and subject to the destructive processes of erosion, which tends to leave little or no direct geological record.

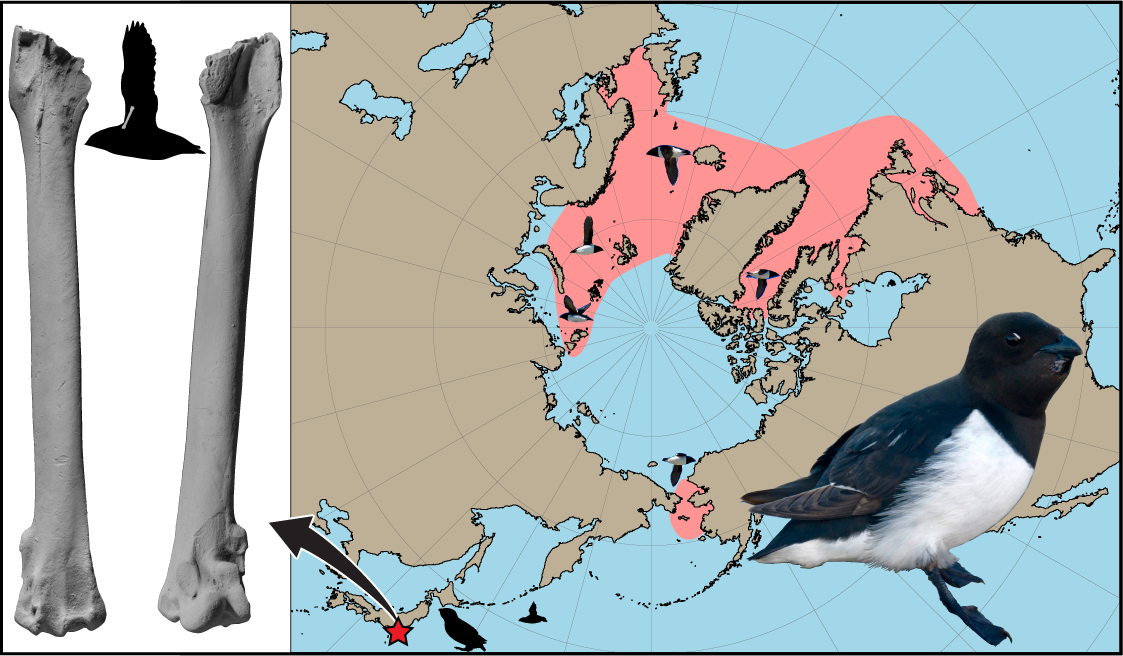

Today the Little Auk is the most common avian predator in the North Atlantic and Arctic Oceans (shown in pink). The fossil bone of a close relative found in Japan, suggests that it was much more widespread 700,000 years ago.

The fossil record

The discovery of mid-late Pleistocene age deposits in Chiba prefecture, central Honshu Island, Japan has provided an unusual abundance of bird fossils, along with the remains of fish, turtles, and mammals, both marine and terrestrial. The Honshu bird fossils include the remains of nine bird species such as ducks, an albatross and an extinct penguin-like seabird called a mancalline auk.

Most interesting, however, is the discovery that a relative of the modern dovekie or little auk was also present around Japan as a member of the seabird community of the North Pacific around 700,000 years ago. Why the little auk should have disappeared from the Pacific and yet be so successful in the North Atlantic and Arctic today is something of a paradox, which researchers hope to resolve as they explore Japan’s bird fossil record. Researchers suggest that present day bird distributions, like that of the little auk, are often just remnants of wider past distributions. Furthermore, investigation of the changes in their distributions will complement the study of historic environmental changes, especially those linked to climate change.

Douglas Palmer

Sedgwick Museum

Additional links:

Watanabe, J. et al. 2020. Seabirds (Aves) from the Pleistocene Kazusa and Shimosa Groups, Central Japan. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. DOI:10.1080/02724634.2019.1697277