Submitted by Dr C.M. Martin-Jones on Mon, 20/11/2023 - 10:36

Cambridge Earth Science’s Professors Sally Gibson and Sergei Lebedev have been awarded a £1 million NERC Pushing the Frontiers grant to explore the processes that create rare earth metals needed for modern technology.

Rare earth elements are used in anything from smartphones and computers to products needed for green energy technologies — including magnets, wind turbines and solar panels.

But rare earth elements are notoriously hard to source — presenting a serious global challenge as demand soars. More than 95% of the world’s usable rare earth elements come from just one mine in Inner Mongolia, China, raising concerns over the security of our supply.

“There is a growing need to identify potential sources that are both closer to home and mined more sustainably,” said Gibson. But, although exploration is seen as essential for long term planning and growth, there is no mine in Europe that supplies rare earth elements.

The new REE-LITH project will investigate why rare earth deposits form in certain locations, providing information that can be used to better guide exploration efforts. “By working with a wider team from the Universities of Exeter, St Andrews, Madrid and Bergen, we hope to create a physio-chemical framework to predict the location of rare earth deposits,” said Gibson.

Rare earth deposits are associated with extinct alkaline volcanoes — tucked away within the interior of the continents and far from the boundaries between tectonic plates where volcanic activity usually occurs.

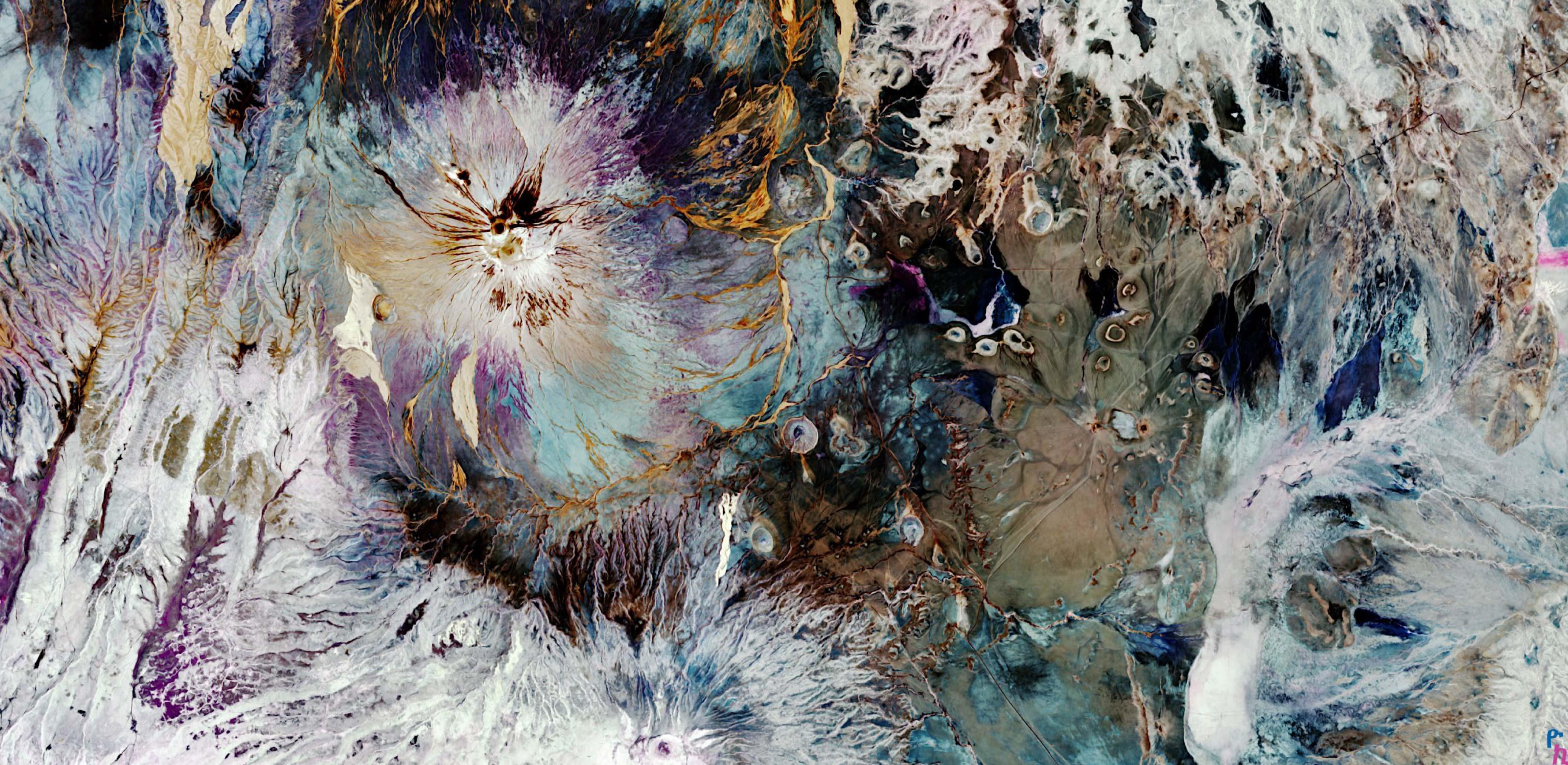

Ol Doinyo Lengai, in Tanzania, is known for its unique, low tempeature alkaline lava. Credit: Sally Gibson.

These alkaline volcanic rocks are relatively unusual, tending to occur only in certain areas. “It’s almost like making up a recipe,” said Gibson, “the thickness of the underlying tectonic plates is a key ingredient.” If the solid outer part of the Earth (or lithosphere) is too thin then basalts are formed. Too thick and instead diamond-bearing volcanic rocks occur.

Europe does have rare earth deposits accompanying alkaline rocks in, for instance, south-west Greenland, Finland and Scandinavia, Gibson noted. But previous studies have tried to explain their occurrence by looking at the surface geology, rather than the underlying lithosphere.

“A key aim for us will be to establish the relationship between the structure of the lithosphere and the occurrence of rare earth deposits across the globe,” said Lebedev. The research will make the most of a recent expansion in the network of global seismic stations, which is helping scientists see the interior of the Earth in greater detail.

Feature image: "Ol Doinyo Lengai, Tanzania" by Yonas Kidane is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.