Submitted by Dr C.M. Martin-Jones on Mon, 27/01/2025 - 11:20

On September 19, 2021, the Cumbre Vieja volcano on La Palma, in Spain's Canary Islands, erupted after more than half a century of quiescence.

Lasting 85 days, the Tajogaite eruption was the longest recorded in the island’s history. Around 12 square kilometres of populated land was inundated with lava, nearly 3,000 buildings were destroyed, 7,000 people displaced and large tracts of economically important banana plantations razed.

For scientists, the eruption presented an opportunity to learn about magmatic and eruptive processes and gather data to help mitigate future volcanic crises.

“This was the first eruption on land on the Canary Islands in the modern, instrumental, era,” said Cambridge Earth Sciences’ Professor Marie Edmonds, “for that reason it is already a very well-studied eruption.”

When Cumbre Vieja erupted, Edmonds and her colleagues travelled to La Palma to the investigate emissions from the eruption. Besides carbon dioxide and sulfur dioxide, volcanic gases may be laced with harmful heavy metals and trace elements which can leach into soils and water supplies and be taken up by plants and animals.

Selenium is a trace element of interest to Edmonds because it plays a dual role, both as a vital nutrient in trace amounts but as a potential toxin when present in excess. Surprisingly little is known about volcanic sources of selenium and its persistence in the environment, said Edmonds, “until recently, the technical difficulties of sampling selenium in volcanic gases, and measuring it accurately in rocks, have limited our understanding.”

As part of a wider project, Edmonds and partners from the University of Waikato and the Open University are using new drone-based methods and geochemical analysis to explore volcanic emissions of selenium during eruptions.

Professor Emma Nicholson from the University of Waikato (previously UCL) led the aerial sampling campaign of the Tajogaite eruption. “Using a drone, we are able to navigate into the eruption plumes and measure the chemical composition of gas emissions in areas that would otherwise be inaccessible,” said Nicholson.

Lava flows covered 12 square kilometres of populated land during the protracted eruption. These flows quickly channelised and began branching, much like braided river systems, and continued degassing during their emplacement and cooling. Video taken on 28 September 2021. Credit: Emma Nicholson, the University of Waikato.

Combined gas and petrology analysis

Alongside these in-situ gas measurements, the team have also been studying the chemistry of the erupted lavas. “Data on gas emissions and petrology are the two crucial pieces of the puzzle in understanding when and how trace elements are degassed into the atmosphere,” said Nicholson.

Volatile trace elements such as selenium are released from magmas as they ascend and erupt, but the extent to which they are available to degas is controlled by magmatic processes deep underground, explained Nicholson.

“We want to know why volcanic eruptions emit varying amounts of selenium in their gas phase,” said Dr Zoltán Taracsák from Cambridge’s Department of Earth Sciences. Some magmas lock away selenium in sulfide minerals rather than releasing it as gas, Taracsák said. The starting composition of the magma is another factor known to control whether selenium can degas.

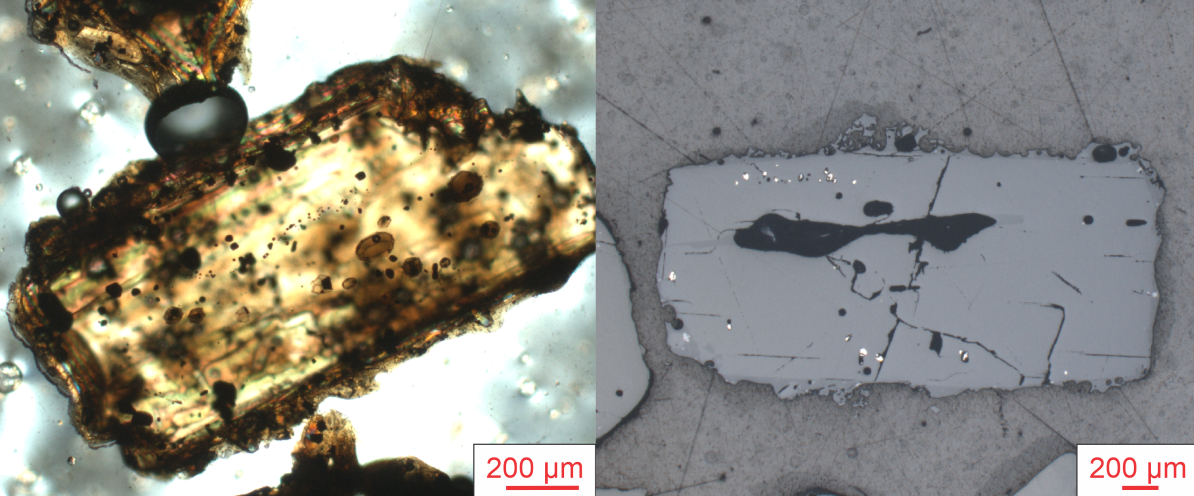

Taracsák has been analyzing tiny pockets of magma that were trapped inside the magma at depth, information that can reveal the magma’s journey to the surface and the conditions required for sulfide mineralization. “How the magma composition evolves, and the point of sulfide saturation, can determine whether these elements are locked into minerals or are instead more mobile in the environment,” said Taracsák, who presented the results of his investigations at the Volcanic and Magmatic Studies Group conference in Dublin this January.

Microscope images showing melting inclusions in the erupted lavas. Top left: melt inclusions, visible as brown blobs, in olivine minerals. Top right: light grey coloured melt inclusions in amphibole minerals, viewed under reflected light. Credit: Zoltán Taracsák.

The researchers hope their investigations of both petrology and gas emissions will help pinpoint the controls on trace element volatility, something that has, “important implications for air quality and environmental hazard during eruptive crises and for the longer-term storage of critical metals within the crust,” said Nicholson.

Edmonds said that the next step in this multi-pronged project is to explore the bioavailability of selenium once erupted, “our investigations will pave the way for larger, integrative studies focussed on the environmental and health impacts of volcanic pollutants like mercury, thallium, and lead, alongside selenium.”

Read more about the SELVES project.

Feature image: Energetic gas-rich explosive activity with substantial volcanic ash production resumes from the northernmost vent on the fissure following a brief eruption hiatus on 27 September 2021. Credit: Emma Nicholson, the University of Waikato.