Submitted by Dr C.M. Martin-Jones on Wed, 08/12/2021 - 10:02

Madi East, second-year PhD student at Cambridge Earth Sciences, is on a mission to help coral reefs — which are threatened by human-induced ocean warming — through improving our understanding of how they grow their intricate and varied skeletons.

Coral reefs are essential for life on Earth — providing unique ecosystems for scores of organisms and protecting shorelines from damaging wave energy. But projections show that, with continued warming and ocean acidification, corals could be wiped out by the end of the century.

Madi’s research will help build a picture of how corals grow under different environmental conditions, part of a wider effort to understand how they will respond to climate change.

Most structures we recognize as coral are actually home to thousands of tiny creatures, called, ‘polyps’. Related to anemones and jellyfish, these polyps secrete a hard external skeleton of calcium carbonate which provides them with a home and gives rise to the branching, brainy or platy structures we see on a reef.

It’s this mineralized skeleton, and how coral polyps build it, that is the subject Madi’s PhD. “My work aims to shed light on this mysterious crystallization process, through the use of geochemical techniques. This will help me get a picture of how the chemistry and structure of corals changes in response to environmental parameters,” said Madi.

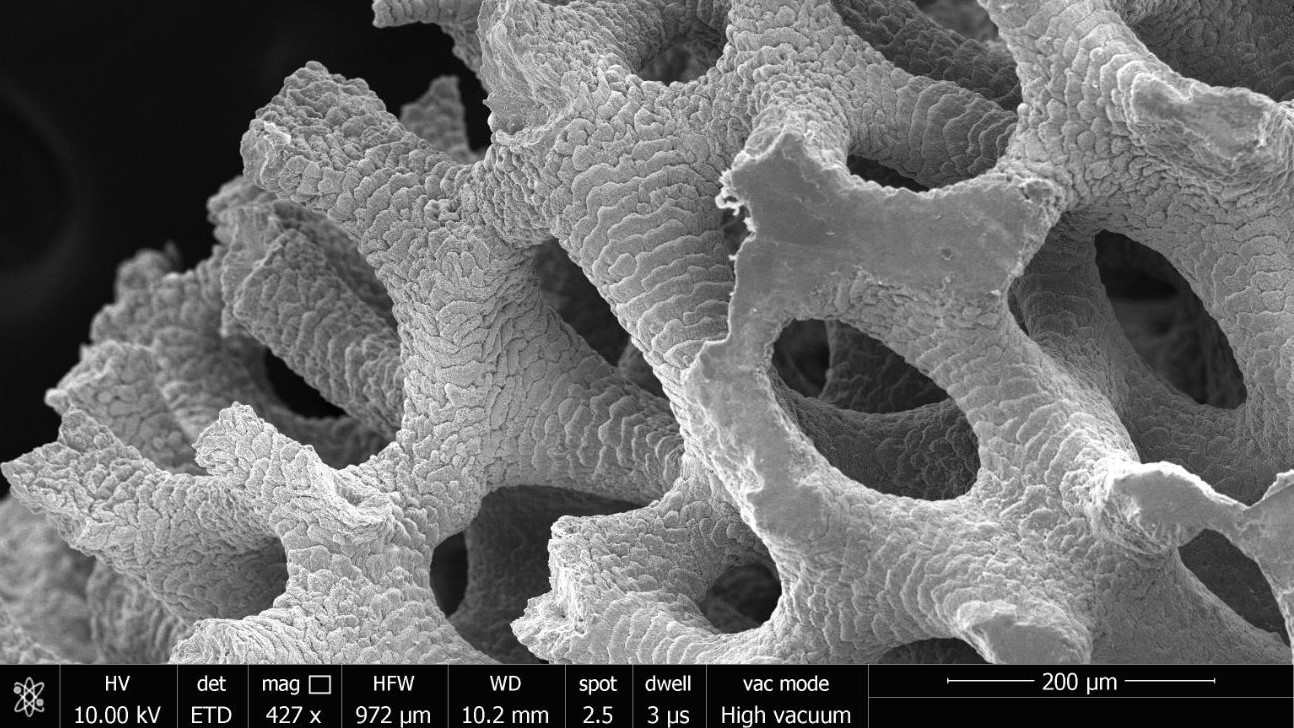

To do this, Madi examines coral samples in detail — using a high powered electron microscope to look deep into the crystal structure. By analysing corals via laser ablation Madi can also build up a picture of how the chemical makeup of a coral can change with the environment.

“I was amazed by how intricate and varied the microscale architectures were… It still amazes me that a colony of individual polyps can coordinate and control the very physical process of crystal growth to create such detailed structures.”

Scientists also use corals as a record of past climate changes. Just like we can read the ice cores to access information on our atmospheric composition, coral chemistry can be used to gauge how ocean temperatures varied in the past. From both the oldest corals in the sea, to those in the fossil record, corals help us put together pieces of the environmental puzzle of the past, from thousand to millions of years ago.

However, some of this record-keeping remains shrouded in mystery. It is thought that biological processes associated with the polyps they host might muddy the climate signal, such that the skeleton is not necessarily recording changes in seawater only. Madi hopes that her work will help shed light on this affect, meaning it can be accounted for in climate studies.

Even though corals are in a tough spot, Madi remains optimistic, “… I hope that in deepening our understanding of this incredible creature, and our knowledge of what climates it has survived in the past, I can help play some part in securing it a brighter future.”

Scanning electron microscope of coral, showing the jagged calcium carbonate crystals which make up the coral's complex architecture.

Read more on our blog.