Submitted by Dr C.M. Martin-Jones on Tue, 01/07/2025 - 14:54

Researchers from the University of Cambridge are using AI to speed up landslide detection following major earthquakes and extreme rainfall events—buying valuable time to coordinate relief efforts and reduce humanitarian impacts.

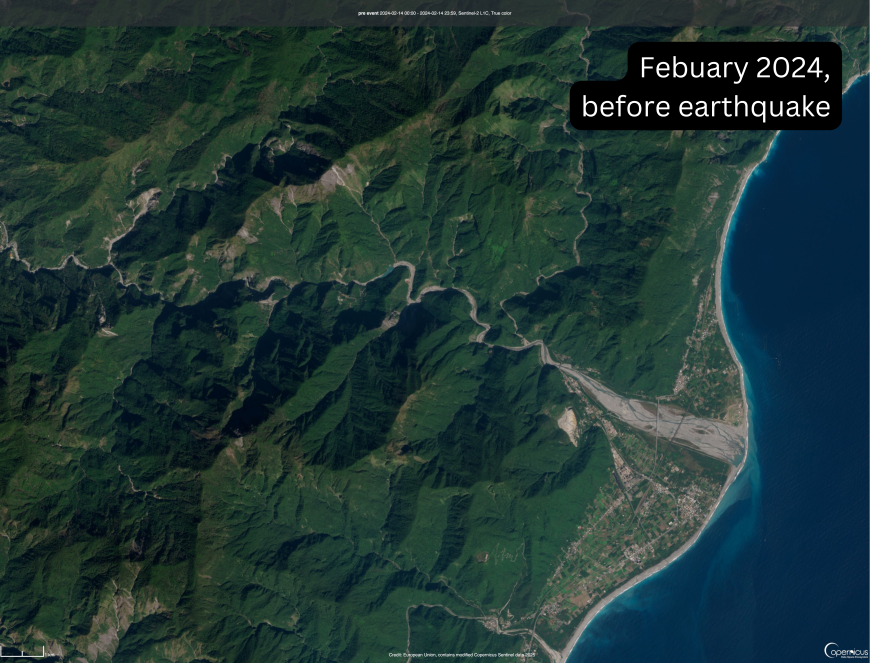

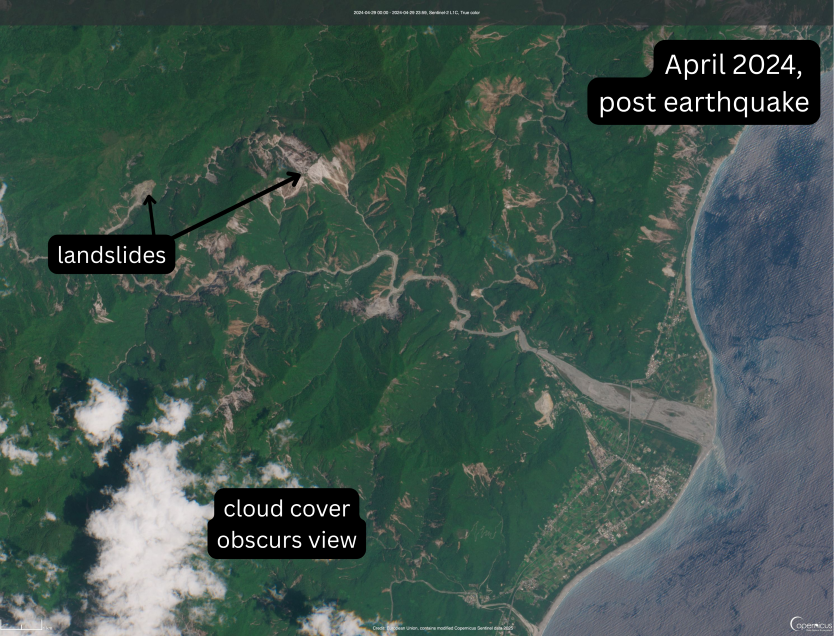

On April 3, 2024, a magnitude 7.4 quake—Taiwan’s strongest in 25 years—shook the country's eastern coast. Stringent building codes spared most structures, but mountainous and remote villages were devastated by landslides.

When disasters affect large and inaccessible areas, responders often turn to satellite images in order to pinpoint affected areas and prioritize relief efforts.

But mapping landslides from satellite imagery by eye can be time intensive, said Lorenzo Nava, who is jointly based at Cambridge’s Departments of Earth Sciences and Geography. “In the aftermath of a disaster, time really matters,” he said. Using AI, he identified 7,000 landslides after the Taiwan earthquake, and within three hours of the satellite imagery being acquired.

Since the Taiwan earthquake, Nava has been developing his AI method alongside an international team. By employing a suite of satellite technologies—including satellites that can see through clouds and at night—the researchers hope to enhance AI’s landslide detection capabilities.

Rescue teams at one of the landslides following the Taiwan earthquake. Credit: Wikipedia Commons/Taitung County Government.

Multiplying Hazards

Triggered by major earthquakes or intense rainfall, landslides are often worsened by human activities such as deforestation and construction on unstable slopes. In certain environments, they can trigger additional hazards such as fast-moving debris flows or severe flooding, compounding their destructive impact.

Nava’s work fits into a larger effort at Cambridge to understand how landslides and other hazards can set off cascading ‘multihazard’ chains. The CoMHaz group, led by Maximillian Van Wyk de Vries, Professor of Natural Hazards in the Departments of Geography and Earth Sciences, draw on information from satellite imagery, computer modelling and fieldwork to locate landslides, understand why they happen and ultimately predict their occurrence.

They’re also working with communities to raise landslide awareness. In Nepal, Nava and Van Wyk de Vries teamed up with local scientists and the Climate and Disaster Resilience in Nepal (CDRIN) consortium to pilot an early-warning system for Butwal, which sits beneath a massive unstable slope.

Nava and Van Wyk de Vries (5th and 8th from left in top image) meeting with local scientists and town planners in Butwal, Nepal.

Improved AI-detection

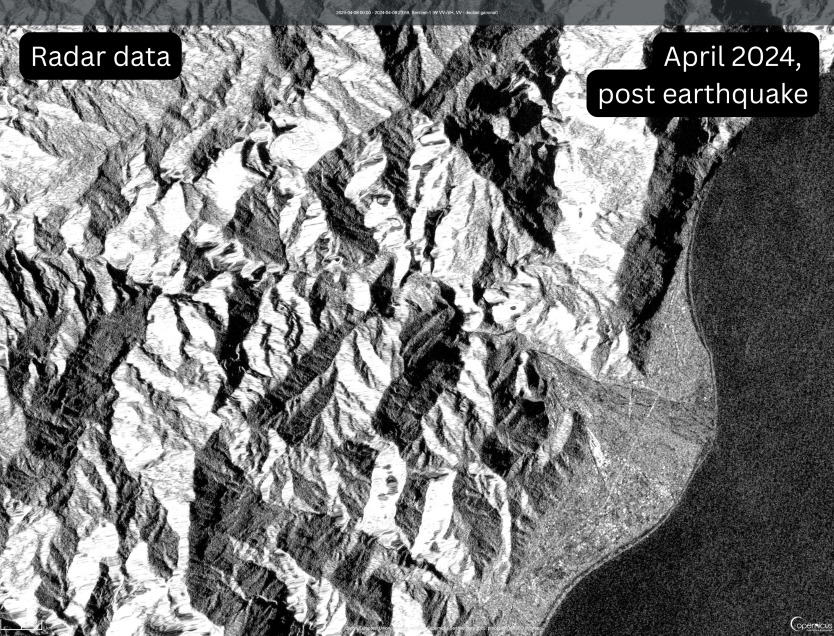

Nava is training AI to identify landslides in two types of satellite images—optical images of the ground surface and radar data, the latter of which can penetrate cloud cover and even acquire images at night.

Radar images can however be difficult to interpret, as they use greyscale to depict contrasting surface properties and landscape features can also appear distorted. These challenges make radar data well-suited for AI-assisted analysis, helping extract features that may otherwise go unnoticed.

By combining the cloud-penetrating capabilities of radar with the fidelity of optical images, Nava hopes to build an AI-powered model that can accurately spot landslides even in poor weather conditions.

His trial following the 2024 Taiwan earthquake showed promise, detecting thousands of landslides that would otherwise go unnoticed beneath cloud cover.

Satellite images collected by the Sentinel-2 satellite, showing optical images collected before the Taiwan 2024 earthquake (top) and after (middle). Greyscale radar data (bottom) can penetrate cloud and see at night. Credit: Copernicus Sentinel data 2024 for Sentinel data, details here.

Nava acknowledges that there is, however, still more work needed, both to improve the model’s accuracy and its transparency.

He wants to build trust in the model and ensure its outputs are interpretable and actionable by decision-makers.“Very often, the decision-makers are not the ones who developed the algorithm,” said Nava. “AI can feel like a black box. Its internal logic is not always transparent, and that can make people hesitant to act on its outputs.”

“It’s important to make it easier for end users to evaluate the quality of AI-generated information before incorporating it into important decisions,” he added.

This is something he is now addressing as part of a broader partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA), the World Meteorological Organization (WMO), the International Telecommunication Union’s AI for Good Foundation and Global Initiative on Resilience to Natural Hazards through AI Solutions.

At a recent working group meeting at the ESA Centre for Earth Observation in Italy, the researchers launched a data-science challenge to crowdsource efforts to improve the model. “We’re opening this up and looking for help from the wider coding community,” said Nava.

The team launching the AI landslide detection challenge. From left to right: Lorenzo Nava, Pierre-Philippe Mathieu (ESA), Hiroshi Ota (ITU), Monique Kuglitsch (Fraunhofer HHI - Chair of the UN Global Initiative), Nicolas Longépé (ESA).

Beyond improving the model’s functionality, Nava says the goal is to incorporate features that explain its reasoning—potentially using visualizations such as maps that show the likelihood of an image containing landslides to help end users understand the outputs.

“In high-stakes scenarios like disaster response, trust in AI-generated results is crucial. Through this challenge, we aim to bring transparency to the model’s decision-making process, empowering decision-makers on the ground to act with confidence and speed.”

Take part in the Challenge:

The Challenge is open to anyone with beginners-level knowledge of coding. More details here.

Further reading: