Submitted by Administrator on Tue, 15/09/2020 - 09:43

A UK-led team of astronomers involving Dr Paul Rimmer, a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Earth Sciences with affiliations at Cavendish Astrophysics and the MRC Labratory of Molecular Biology, has discovered a rare molecule – phosphine – in the clouds of Venus, hinting to the possibility of extra-terrestrial life.

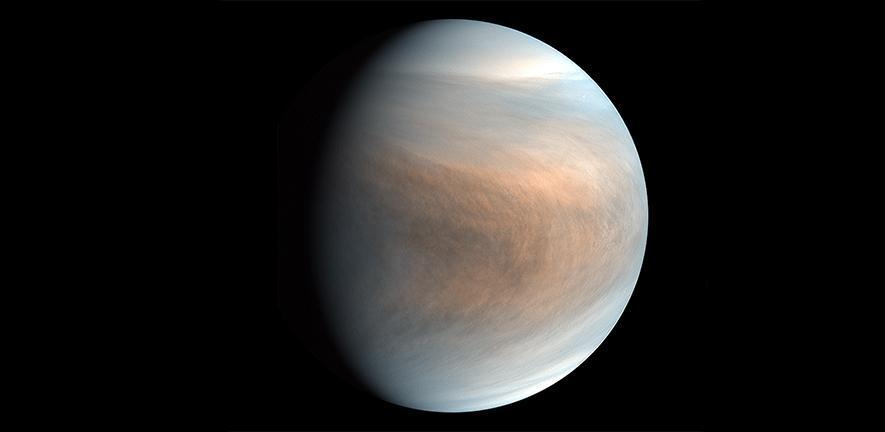

Astronomers have long speculated that high clouds on Venus could offer a home for microbes – floating free of the scorching surface, but tolerating very high acidity. The detection of phosphine molecules, which consist of hydrogen and phosphorus, is an important step in the search for life beyond Earth, a key question in science. The results are reported in the journal Nature Astronomy.

“This discovery brings us right to the shores of the unknown,” said Rimmer. “Phosphine is very hard to make in the oxygen-rich, hydrogen-poor clouds of Venus and fairly easy to destroy. The presence of life is the only known explanation for the amount of phosphine inferred by observations.”

The discovery was made by Professor Jane Greaves while she was a visitor at the University of Cambridge’s Institute of Astronomy. Greaves and her collaborators used the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT) in Hawaii to detect the phosphine, and followed up their discovery on the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. Both facilities observe Venus at a wavelength of about 1 millimetre, much longer than the human eye can see.

“Both observatories identified the same thing – faint absorption at the right wavelength to be phosphine gas, where the molecules are backlit by the warmer clouds below,” said Greaves.

“This was an experiment made out of pure curiosity, really – taking advantage of JCMT’s powerful technology, and thinking about future instruments,” said Greaves, who is based at Cardiff University. “I thought we’d just be able to rule out extreme scenarios, like the clouds being stuffed full of organisms. When we got the first hints of phosphine in Venus’ spectrum, it was a shock!”

Using existing models of the Venusian atmosphere to interpret the data, the researchers found that phosphine is present but scarce – only about twenty molecules in every billion. The astronomers then ran calculations to see if the phosphine could come from natural processes on Venus.

On Earth, phosphine is only made industrially or by microbes that thrive in oxygen-free environments. Co-author Dr William Bains from MIT ran experiments to test if phosphine could be naturally manufactured on Venus. Bains tested a range of factors including; sunlight, airborn minerals, volcanoes, or lightning - but none of these could make anywhere near enough. Natural sources were found to make at most one ten-thousandth of the amount of phosphine that the telescopes saw.

They caution that some information is lacking – in fact, the only other study of phosphorus on Venus came from one lander experiment, carried by the Soviet Vega 2 mission in 1985.

“These facts lie at the edge of our knowledge: the observations could be caused by an unknown molecule, or could be caused by chemistry we’re not aware of. Ultimately, the only way to find out what's really happening is to send a mission into the clouds of Venus to take a sample of the droplets and look at them to see what's inside”, said Rimmer.

According to Rimmer, in order to create the observed quantity of phosphine on Venus, terrestrial organisms would only need to work at about 10% of their maximum productivity. Any microbes on Venus will likely be very different from their Earth cousins though, to survive in hyper-acidic conditions.

On Earth, bacteria can generate phosphine as they metabolize, taking in phosphate minerals together with hydrogen. It costs them energy to do this, so why they do it is not clear. The phosphine could be just a waste product, but other scientists have suggested it may act to ward off rival bacteria.

Co-author Dr Clara Sousa Silva from MIT says “Finding phosphine on Venus was an unexpected bonus, the discovery raises many questions, such as how any organisms could survive. On Earth, some microbes can cope with up to about 5% acid in their environment – but the clouds of Venus are almost entirely made of acid.”

Other possible signatures of life may exist elsewhere in the Solar System – take the methane on Mars and water venting from the icy moons Europa and Enceladus. It has been suggested that the dark streaks in Venus’ clouds, which are caused by the absorption of ultraviolet light, might host microbial life. The Akatsuki spacecraft, launched by the Japanese space agency JAXA, is currently mapping these dark streaks to understand why they occur.

The team believes their discovery is significant because they can rule out many alternative ways to make phosphine, but they acknowledge that confirming the presence of ‘life’ needs a lot more work.

The high clouds of Venus have temperatures up to a balmy 30 degrees Celsius, but they are incredibly acidic – around 90% sulphuric. The question remains as to how life could sustain such acidic conditions. The team is no going on to investigate the possibility that the microbes could shield themselves inside droplets.

Reference:

Jane S. Greaves et al. ‘Phosphine Gas in the Cloud Decks of Venus.’ Nature Astronomy (2020). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-020-1174-4

Adapted from a University of Cambridge press release.